A few years ago I started work on a novel: The Man Who Bought a Pier. All planned out, I’d completed the first 10,000 words before the project came to a stop (though I can’t remember exactly why). In my recent trawl through past lives, I have resurrected the opening again to see if it might yet have ‘possibilities’.

The story is magic realism, a genre I have worked in once before: my comic novel The Big Frog Theory (started in 1994 and eventually finished nearly twenty years later). It had been great fun to write, and consequently I’ve had a bit of a hankering to revisit the genre. Indeed, there was a sequel to Frog planned - Mita’s Shopping - but that didn’t get very far either... [Yes, I know; my writing life is littered with unfinished projects! (see Shrapnel from a Writing Life).]

Anyway, here is the draft opening of Pier… (there’s more, if anyone’s interested)

One

In the end, he was disappointed with how little of the interview they had shown on television. He had been there hours it seemed, take after take, facing simple questions to which he found himself giving detailed answers because he wanted them to understand. They seemed frustrated with him, expecting him to conform to the programme’s modus operandi rather than tell the truth. They wanted something short, punchy and sensationalist — after all it had been a consumable event of some merit from their perspective. He could see them thinking that if they covered it in the right way they might make the national news. But his story was far more complex than that.

His favourite quote they had, unforgivably, cut altogether.

“It’s not” he had said “about who is chosen and who is not. It’s more random than that. It’s about who happens to be there at one precise moment; at the point when it begins, and from which there is no going back.”

Even if they chose to ignore it, there was no way he could forget that moment; his moment.

Subsequently his friends had used various words when they found out what he had done, the circumstances of his purchase. Now he found himself wishing he had kept some kind of tally. ‘Amazing’ had been popular, along with similar terms all used to express wonder; after all, how many people had bought a seaside pier?! He filtered out memories of those who had said he’d been stupid, that he shouldn’t have been surprised at the outcome. Yet it wasn’t as if the pier had cost him vast sums of money. A pound. On the news he’d heard of whole companies changing hands for a pound, so why not a pier?

That it had been an accident was beyond question, even though he eventually distanced himself from that notion. His idea about being ‘chosen’ was not one that had come instantly to him; subsequent experience which led him to formulate the premise, and partially he did so out of necessity, to try and explain things away. Perhaps it was also a defence mechanism as much as anything else.

“I’d stumbled across this old building on the edge of a car park in a neglected part of town. I’d never been to ____ before, so had no idea what it was. The building, I mean. The front doors were open and so I went in, partly to shelter from the weather as it had just begun to rain. It was only a shower, but I thought I’d see it out under cover before heading for the museum and art gallery, which was why I was there in the first place. There were a few people milling about inside, either huddled in little groups or scattered amidst a range of tables, chairs, old wardrobes. Many of the tables were covered with crockery, cutlery, odd boxes of jumble most of which had seen better days. There were paintings and prints hanging on the walls, and as I adjusted to the scene I spotted other, more obscure things: a full-size stuffed black bear, for example. And then I heard a voice and the bang of a hammer. Or it might have been the hammer first and then the voice. Whichever way round, I knew then it was an auction house. Once I had that reference point to navigate by, I took in the whole room again. Suddenly all the junk and the clutter made sense; and all the furtive-looking people too. I wandered further in as the auctioneer introduced the next lot; watched the bidding; heard the hammer fall again. At some point someone gave me a laminated sheet of white card with a number printed on it: ‘427’. As I watched the next lot sell — a faded old three-piece suite — I understood what the number was for. I hadn’t asked for one, and didn’t need one. Or at least I didn’t think I did.

“It was a fascinating experience, just watching. You could tell the experienced auction-goers; the way they timed their first bid, how they delayed their responses. Often I’d imagine there would be no bid at all on something, and then just as you thought time was running out, wham!, they’d be in there with some ludicrously low offer. I was amazed how often the Auctioneer tried to start the bidding at, say, fifty pounds and then get no interest until he was scraping the barrel at five. Then suddenly everyone was in, and the thing would eventually sell for seventy or eighty. That didn’t make sense to me. And the bidders each had their own unique way of lodging their bids: the little flick of the brochure or their white card; a nod of the head; even a wink. Some were demonstrative, but most weren’t. It was if they were doing something illegal, something to be embarrassed about.

“The lot numbers rose rapidly. I’m sure they were in the three-hundreds when I walked in, but then suddenly they were in the four-twenties, creeping towards my number. I was intrigued to see what was on offer in lot four-two-seven.

“‘Lot four-hundred-and-twenty-seven,’ said the dapper Auctioneer, scanning he room as he did so. ‘A rather unusual item: the pier at West Beach. Built in eighteen-sixty-one, last used commercially in the seventies. In reasonably good repair, considering.’ He checked some notes on the lectern in front of him at this point. ‘Nothing on the book. My instruction is that it must sell. So, where shall we start? Ten thousand?’ There was a little ripple of laughter from my right. I turned but couldn’t see who it was. ‘A thousand? Five-hundred?’ As he gradually dropped the price I scanned the room, trying to guess who might be the first person to bid. ‘Two-hundred?’ No-one seemed interested. From the back of the room there was a clatter of crockery from the small galley kitchen serving tea and coffee. ‘Fifty pounds? Surely it’s worth fifty? Just to get us away.’ Still there was nothing. The place seemed suddenly quiet, eerily so, as if everyone was afraid of making noise or movement in case the Auctioneer saw it as a bid. There was palpable tension in the room. Thinking about it now, I recall how struck I had been by it. ‘Ten? Alright, five?’ He glanced down at his notes again as if he was checking something. When he looked up, he was staring straight at me. ‘If I must… One pound?’

“To this day I have no idea how I managed to bid. I don’t recall sneezing, or winking, or making any kind of movement that could possibly be interpreted as a bid. Maybe someone nudged me, I don’t know. But he suddenly said — still looking at me — ‘One pound bid. Do I hear two?’ Believe me, at that point no-one wanted to hear ‘two’ more than I did! But there was nothing but silence. Nine seconds of silence. I counted them. And then down came the hammer. Lot number four-hundred-and-twenty-seven, bought by the man holding card number four-hundred-and-twenty-seven. For one pound.

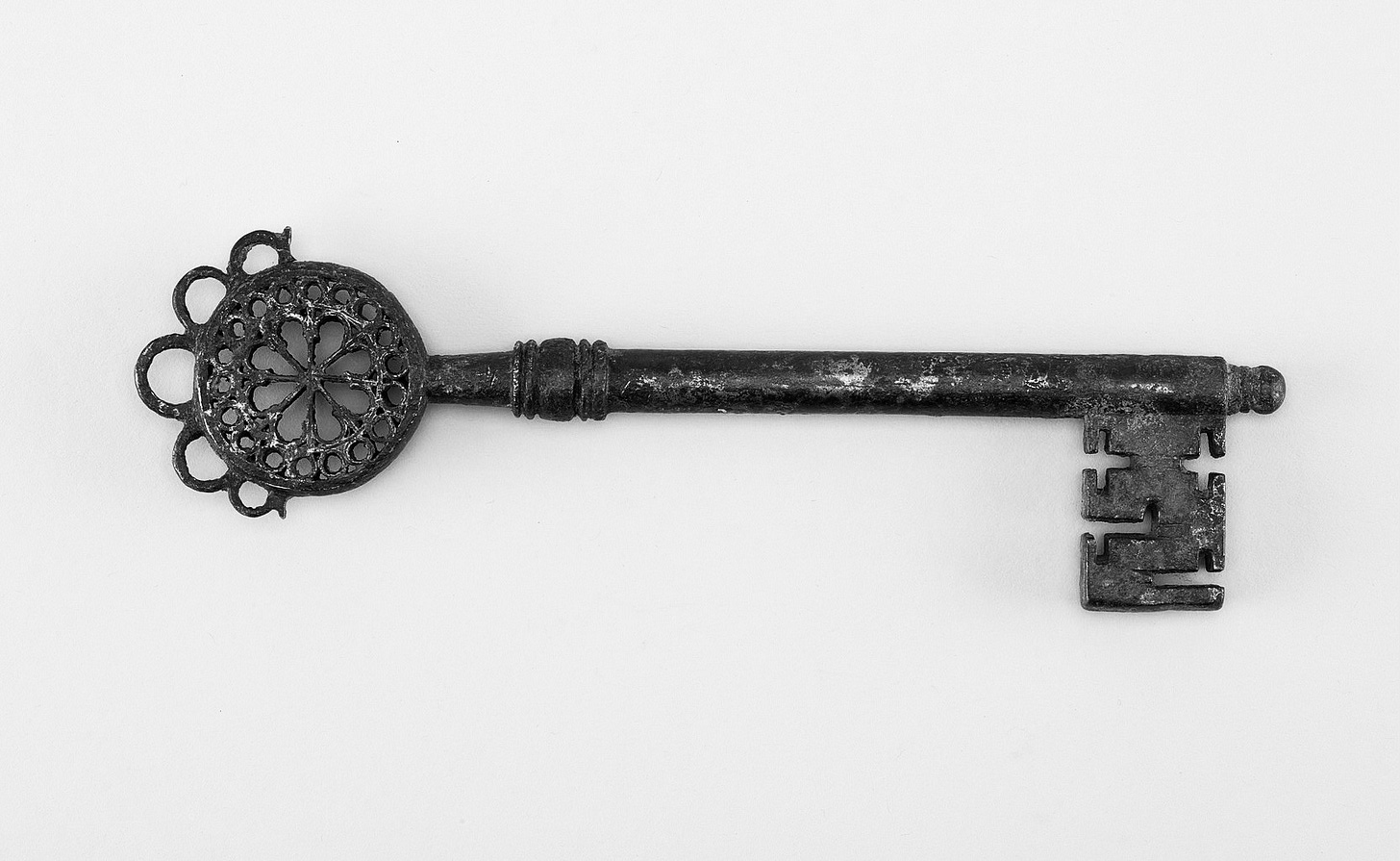

“Afterwards I tried to get out of it, saying there had been some kind of mistake, that I hadn’t meant to bid. But they weren’t having any of it. ‘Look at it this way,’ the Auctioneer said as he handed over a set of misshapen keys, ‘it’s only a pound; what’s the worst that can happen? If you want to, you can submit it in next month’s sale. You might even turn a tidy profit. Or even a little one.’ His laugh told me that he didn’t believe that at all, and perhaps he had reason not to. But there was nothing malicious in his face; in fact, it was almost the opposite. For an Auctioneer, he gave the impression of appearing exceptionally benevolent. I hadn’t thought much about Auctioneers at all until that afternoon, but would probably have seen them as shifty, out to make a quick buck. A bit like second-hand car salesmen. But Charles Thomas — that’s what his name badge said, as did the sign on the building outside — seemed entirely trustworthy. He wasn’t laughing because he had taken me to the cleaners (and all for a pound!), but because he thought the idea of manufacturing a profit from an old pier was mildly amusing. As if to prove his trustworthiness, when he took my pound he gave me a receipt to go with the keys. Then we were all ushered out of the hall. As I stood outside in the car park feeling profoundly alone, I heard the doors close behind me with a strange kind of finality. The illuminating lights behind the words ‘Charles Thomas’ flickered out.

“I felt a bit of a chump; an idiot who had just acquired a set of old keys and, almost certainly, some rotten, rusting, dangerous structure jutting out into the North Sea.”

Oh wow, i would certainly read this! Hope you continue.