A house filled with history and secrets is more than mere bricks and mortar; not only a mirror on the past, it can also be a window to the future.

“masterful..soul-searching. I would have liked to live next door to Owen and Maddie; I feel we would have been friends” – Siobhan Gifford

“a dextrously woven story of how the complexities of any given life remain with us, and remain too within the bricks and mortar that bore witness” – Jonty Pennington-Twist

”a beautifully crafted story” – Janet Burl

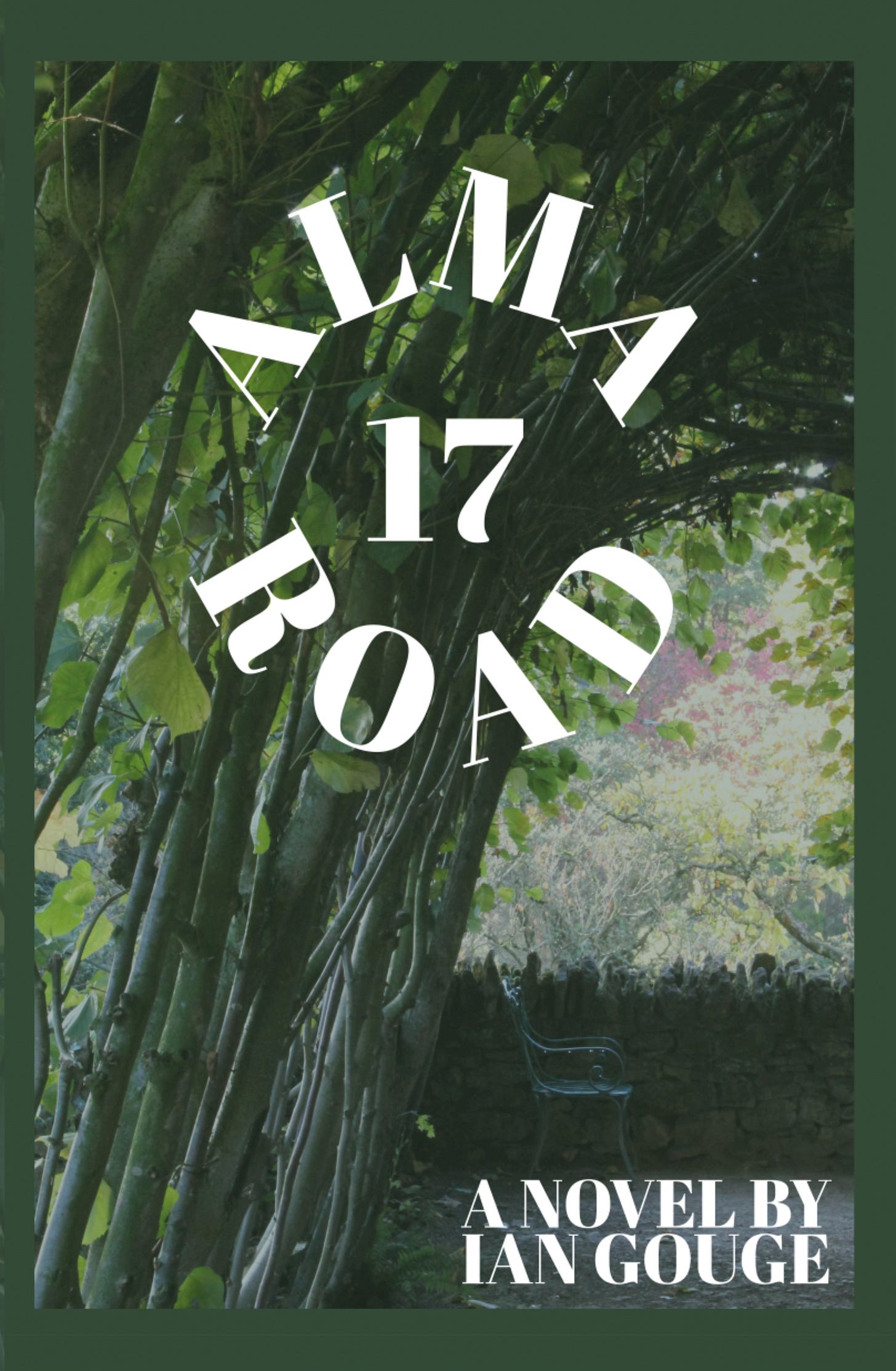

And the house itself? Apparently intact. The sash windows look sound and the front door is as dark and solid as he had always known it. The lime render has cracked a little here and there, and in some places it too has been usurped by nature, a combination of climbing hydrangea and darker ivy seemingly in a race to the gutter at the top of the house, a race he is confident the ivy will win. The overall effect is somewhat taking however, and he is sure that anyone who might glance over the wall would regard the general facade as charming — even if such a sentiment would immediately be chased away by regret that the house has fallen into neglect. Indeed, it is hard to escape the fact that the place is letting the street down somewhat, playing odd-one-out with an array of neatly clipped hedges, well-tended gardens. Against such a model of comfortable suburban existence, were such onlookers of an imaginative or speculative disposition they might also have attempted to sketch out a history for the place and wondered, given the nature of its surroundings, how the house had come to this — and then simply carried on walking, always supposing the house had been worthy of them breaking stride in the first place. The more commercially-minded might just have wondered what it was worth.

But he knows most of the house’s recent history — it is as much his story as the house’s after all — and so can chart the journey from how it had been when he had lived there to how it stands today. There are episodes which inevitably elude him, fragments where he lost touch with the house as much as he did its inhabitants, though not through disinterest but because he was out of the country, wrapped up in other houses, other gardens. And other victories and defeats? Inevitably.

And ‘worth’; how might you quantify that? “Not everything can be easily measured in pounds, shillings and pence” his aunt had once said to him as they sat in front of the fire. Even now he can picture the scene, and vaguely recalls that at the time he had been young enough to qualify as a child yet old enough to be on the threshold of beginning to understand the value of money. And “pounds, shillings and pence”? That leant a date to the incident: before 1971. But only just. He turned six in 1971, almost simultaneously with the country’s shift to decimalisation. For a while ten or fifteen years ago he had wondered if he might be witness to a second such migration — from the pound to the euro — but this never materialised, much to the chagrin of Maddie and the delight of his aunt.

Florence once described herself as ‘an Empire girl’, bound-up in the traditions of a Britain long since vanquished. If the general populous had been weaned off such notions during the latter part of the twentieth century, there were many things to which Florence seemed determined to cling. Wreckage or not, if the pound had fallen (and, as she saw it, “to the Germans, of all people!”) then he sensed she might have sunk along with it — and what would that have said about the rest of them? The fact that she had managed to hold on for another few pragmatic years — until a massive stroke did for her that black Thursday just as she was wheeling her shopping out of Waitrose — demonstrated both longevity and perseverance. The sudden nature of her end led some at her funeral to confess themselves grateful — such a passing was “a blessing” — although one or two of her erstwhile friends were secretly glad to see the back of her.

Did he miss her? Even if it would have been an entirely redundant question, he had imagined Maddie asking “Do you miss her, Glen?” soon after Florence’s death. Although christened Owen, Maddie had chosen to call him ‘Glen’ ever since a history lesson at school during which she had been introduced to the legendary Welsh soldier and nationalist, Owen Glendower. Not only were they not Welsh, the young Owen showed no indication that he would make either an effective soldier or nationalist. Maddie had simply liked the sound of the words together.

“Don’t we all?” he might have replied, his answer to her question implicit in his own.

And does Owen still miss her now — Florence, that is — as he stands looking up at the first-floor windows: the one that had been his, Maddie’s next to it, Florence’s on the end?

She and George had been ensconced in that room when he and Maddie arrived bereft and unwanted in the summer of 1969, suddenly-orphaned children who, when faced with being thrown upon the mercy of Social Services’ bureaucracy, found themselves rescued by their Aunt and Uncle. Alice, their mother, had been an only child, and Florence was their father Augustus’ only sibling. Such dramatic consequences would have been far from the mind of the inebriated lorry driver who, on rounding a blind bend too much outside of his lane, met their parents’ car head-on. It had been a moment of madness which had not only killed its occupants in a brutal collision, but unravelled all that had gone before as well as the future plans already laid out for all the members of the family. As a quartet they had more or less mapped out the next twenty years, all the way through to Maddie’s graduation from a university somewhere unspecified, proudly following in her big brother’s footsteps. Given they were just four and two respectively, he and Maddie had been too young to make any contribution to the conversations which led to such conclusions; but Augustus and Alice had been progressive enough to ensure that their children were at least in the same room in which the relevant conversations were taking place even if they could have no possible idea what was actually bring discussed. Perhaps it was not surprising that Florence and George were made of similar stuff, shared the same aspirations for their nephew and niece; so much so that in the end their parents’ tragedy impinged on the children for less than a year — at least in a practical sense. It was, to be sure, a year of upheaval and trauma, trauma and upheaval, but once they had settled down — the four of them — a new kind of normality took over. As Florence and George became their de facto parents, memories of their real mother and father faded quickly. If Maddie chose on occasion to suggest she could still remember them, Owen let her indulge her fantasy. For his part, he recalled nothing.

All of which means there is no existing connection between the house before him now — Florence and George’s house — with Augustus and Alice other than an increasingly remote familial tie. Although hardly possible in his parents’ case, he has an inkling that the rest of them might have left a ghostly imprint somewhere about the place, a tangible spectre that — if he chose — he could lift and examine as easily as he had raised those small chunks of rust from the limestone coping. And could he? Should he? Is that, after all, why he is standing here now, hand once again on the garden wall, his eyes scanning the scene almost as if he were looking for clues? Does Owen need the house to respond to his prompting? Or does it work the other way round, the house and garden as the catalyst for memory, precisely as that far bedroom window made him think of Florence in a concrete way — and for the first time in what seems a very long time?

Are any of those questions resolved before he reaches the front gate and leans against it just to see?