As I was trying to get back to sleep this morning (before I gave up and came down to my study an hour earlier than I’d intended) it stuck me how many remarkable things I had done in my life. And that it can be good to stand back and take stock.

I have taught in West Africa; lived and worked in Switzerland and Singapore. I have travelled the world: the USA (all three time-zones), Grenada, Eire, Finland (many times), Sweden (many times), Denmark (many times), Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France (many times), Spain, Italy (many times), Greece, Sierra Leone, Kenya, India, Indonesia, China, Japan, Australia.

I have been homeless (as a child); lived in nearly 40 different houses (but in reality perhaps only two or three homes); got a degree; as a young man, loved and lost too often (haven’t we all!); been married twice; fathered three children; made and lost friends; managed teams of c.150 people (internationally) and annual budgets in excess of c.£18m.

I have been ‘political’ (small ‘p’) and stood for election (in both local government and trade union back in the day). I have been a school governor and trustee for a charity, and I have discovered a life-long love of sport, art, cinema, music, theatre - and literature, that saving grace.

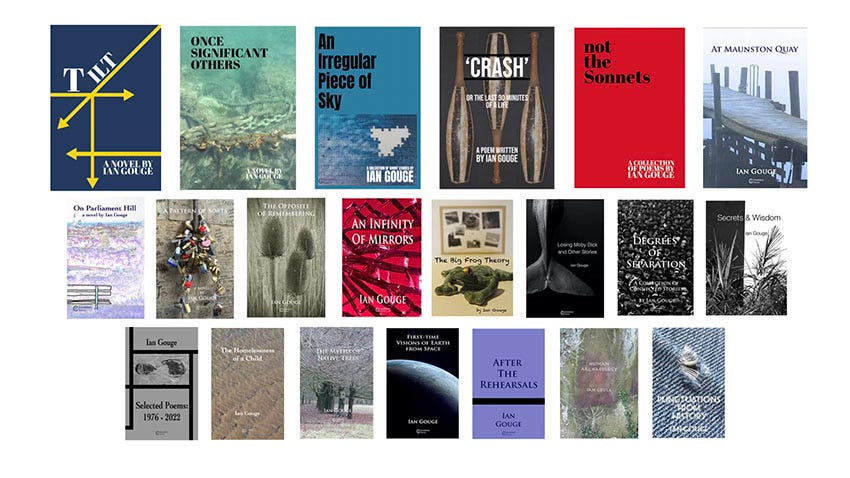

And I have written over twenty books, and published over twenty others (the grand total of both will exceed fifty during 2024).

Not a bad cv I hope.

And in taking stock, I realise that I have no real desire to add much to my tally of global places visited - and I certainly don’t intend to marry again, father any more children, or move house again (probably!). I’m quite satisfied, thank you very much.

But books?

I’d love to write another twenty. Or thirty. Each and every one of them will be fuelled by the experiences curated from the life putting together that cv above. How can they not be? I doubt I’ll last long enough to write as many as I’d like - though that won’t stop me from trying…

And in case you missed these posts…

17 Alma Road

IX Even though he was there just four years previously, that visit is sufficiently distant for Owen’s immediate impression to be one of him crossing the threshold of a house which is both larger and darker than he remembered it. Removal of the furniture had insured the first, and the few remaining curtains being left partially closed guaranteed the second. Standing in the hall, the front door shut behind him, he allows his eyes to acclimatise to the subdued light before walking to the foot of the stairs unable to miss the silhouette on the landing above him where one of Maddie’s larger paintings had hung. Casting his gaze around the hall he sees similar rectangular and square traces everywhere, and tries to recall which art work had adorned which wall. Believing he should be able to do so, he feels a failure when he cannot.

After All This Time

After All This Time Have you noticed how, on cold but crisp autumn mornings, if you stare at the low sun and scrunch-up your eyes you can make it look as if there’s mist laying low over the land? Yet if it is a truly misty start to the day, no matter how wide you open your eyes, the mist never goes away. Why is that? Surely logic would suggest taking an opposite action should generate an opposite reaction. Isn’t that Einstein? Or perhaps a case of ‘some you lose, and some you lose’? I don’t know. It just strikes me as odd, unbalanced, out of whack. But then lots of things do I suppose, if you take the time and trouble to think about them. Having said that - and have you noticed how, as soon as you say one thing, another immediately pops into your head, often to baldly contradict what you had previously thought, as if there is a part of you determined to undermine yourself, to always dispute and ridicule, to disprove what you say and think and believe so that you don’t actually know what’s right any more? Anyway, having said all that about taking the time and trouble etcetera, most people don’t have any spare, do they? Time, I mean, not trouble. Certainly not enough sloshing around for them to be squinting up at the sky. They’ve got more important things to do, deadlines to meet, trains to catch, mouths to feed, bucks to earn, clothes to buy, drinks to drink, dogs to walk… And not doing things takes time as well because we have to think about those too, deciding