Bruised

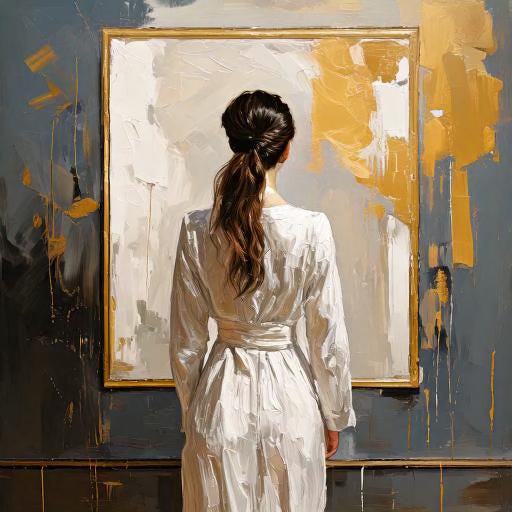

She is cursed. Standing before the mirror, she runs her left hand through her hair, glances down to her left shoulder; and even though she cannot see herself, she knows doing so will lift what she is wearing just a fraction, make taut the thin material wrapped about her, and bring into sharper relief the outline of her right breast, its slightly too-dark nipple.

For whom does she make this gesture, create this image? Not for herself, because she has seen it often enough in photographs; nor for those who took the photos, or those that viewed them. And though she might have, nor does she strike the pose for someone nearby, watching perhaps from the bathroom door.

At first merely downcast, she now closes her eyes and tries to imagine what she might see if she were able to conjure an out-of-body experience, if she could be standing in the doorway peering in. But then she knows what she would see too: a woman of exceptional beauty who has so often been told that she is perfection personified that the words now lack meaning. She is, they said, the kind of woman who can fill a man’s dreams and take him out of himself — though to where no-one ever acknowledged. But these are hackneyed notions now, as is the pose; a cliché as relevant as yesterday’s news, as meaningful as a puzzle clue a five-year-old could solve.

So what does she see then? Ah yes, a woman cursed; a woman who has been turned into something else, something she is not, simply because she knows how to incline her head, raise a shoulder, emphasise an outline through diaphanous material. Once that person was her, she knows that. Once she revelled in the attention, was happy to strut, to exaggerate, to play the role of the woman who could take men to other places — and not only in their dreams. She knows she embraced this, became addicted to the clamour, the demands on her, the flash of cameras, the red carpets, and the parties which followed the red carpets.

Promises and propositions crept insidiously into her life, each one edging beyond a boundary established by the previous. She could be this or that, she could have this or that; all she had to do was… But then she knows what she had to do. Standing there, eyes closed, pose held, she knows what she did do, the boundaries she crossed; and she understands how, once crossed, there was no going back. I made a mistake was never a plea that would be listened to, not in the cacophony of you did that, so why not do this? And even though she did not want too (or that is what she tells herself) she acquiesced time and again: the garments became skimpier, the fabric more flimsy, until there was no longer any fabric at all. And after that, what else could she give them?

They were only too willing make suggestions.

So she does not need to see. Nor does she need to open the cabinet to find the evidence, examine the subtle marks on her arms, the newly incurred bruise which will bloom soon enough. She bruises so easily these days! Rather, she needs to feel again, to remember the person she had been ‘before’: before the compliments, the first shutter click, the first photo in the local paper, the first invitation, the first suggestion, the first contract. There was only one first yes, she recognises that now; a ‘yes’ which spawned a whole cavalcade of ‘yeses’ as if they began to breed in spite of her, as if she was their host and not their mistress.

These were the base elements of the curse. She gave them two things — her physical being and her yes — and they proceeded to take everything else. Except…

Except today she has already said no. And having done so, she has walked into her bathroom to look at herself in the mirror, to cross-examine her physical self — indeed to see if she can understand what all the fuss has been about — and she has recognised the truth. Eyes closed, head still bowed, she relaxes her shoulders, trying to imagine what it will be like to eventually be released. It is a journey on which she has now embarked, taken the first small step. Perhaps — as with that first yes — fate has already set her path; what will follow is another logical sequence, and she wonders how different it will be, a journey predicated on ‘no’ rather than ‘yes’.

Years ago she had assumed that saying yes was demonstrating her control, the exercise of free will; but now she knows it was no such thing. In order to lift the curse, she has realised she must take the opposite view, that saying no is a more powerful statement of her independence. When they ask to see her pose she will say “no”; when they ask her to remover her clothes, “no”; when they suggest they know someone in Hollywood who is interested in casting her in a film… “No” and “no” and “no” again. That is exercising choice, demonstrating independence, and the only way to lift the curse.

And that first step? That first no? Standing upright, she looks at herself in the mirror again. From the corner of her eye she notices a small spot of red on the edge of her top. She will need to dispose of the garment — in the same way as she will need to dispose of Glynn who lays crumpled on her tiled hall floor. She has already decided it was not unusual that he expected her to say ‘yes’, but he had made his approach in such a violent and malevolent way — and at the very moment when she had decided she didn’t want to be a puppet any longer — that he felt the full force of her first no. In spite of how badly he has treated her over the years, she feels sorry for him, the impact of that fateful coincidence. She had bought the gun and kept it in her bedside cabinet for an unspecified reason. And now its purpose was fulfilled: the instrument of her first no; the deed done; the beginning of the lifting of the curse.

So she will get dressed, make the phone call to the police, claim self-defence, show them the bruises on her arm, prepare to put on another act.

After all, she’s good at that.